Boston, MA (CNN) — Sometimes, implementing wide-reaching social change takes surprisingly few materials. With just a handful of bike gears, MIT professor Amos Winter is hoping to change the developing world forever.

Boston, MA (CNN) — Sometimes, implementing wide-reaching social change takes surprisingly few materials. With just a handful of bike gears, MIT professor Amos Winter is hoping to change the developing world forever.

Winter is the inventor of the Leveraged Freedom Chair (LFC). It is a low-cost wheelchair powered by two hand levers that function in a similar manner to gears on a bike. The higher you grab it, the more leverage you get when traversing over rough terrain like sand, mud, or unpaved road.

Grab down lower, and the machine can cruise along tarmac at five miles-an-hour. It is one of the most versatile wheelchairs on the market, and for the time being, it is aimed solely for disabled communities in the developing world.

“If you are a wheelchair user who lives in a rural area, there’s not really a good mobility aid that allows you to travel a long distance on many types of terrains, but is also small and maneuverable to use indoors. That is kind of what set the stage for creating the LFC,” says Winter.

It may seem like a simple premise, but the LFC has the potential to empower a community that, in poorer countries, can often feel disenfranchised.

Read: Is this what the future holds?

“As this technology has grown and become a product, it’s been very fulfilling to see that not only can people ride off-road, but having that capability also lets them have a job, or go to school or fully participate in their community,” says Winter.

What makes the LFC a truly invaluable tool in low income communities is its sheer value for money. Traditionally, wheelchairs with the capability to go off-road clock in somewhere between $4,500 and $6,500, making them prohibitive to the rural communities that need them the most. The LFC, by comparison, costs $200.

The low price point, explains Winter, makes it a sexier sell to the non-profit organizations responsible for delivering these units to emerging markets.

“It had to be cheap enough to fit within the current provision and donation structures that already distribute wheelchairs,” he says. Furthermore, Winter recognized that to be of use to the developing world, it had to be built from parts that were easily accessible.

“The chair not only had to be repairable, but we wanted it robust,” he says. “We wanted it to have minimal parts that could break in the field, but if the parts do need servicing, they’re made from bike parts and they’re easily available.”

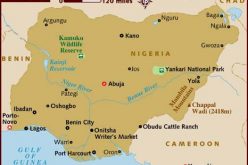

Winter’s inspiration for the LFC came about in 2005, when he spent a summer in Tanzania assessing wheelchair technology for a group of wheelchair organizations. He later started developing the technology as a graduate student at MIT.

Read: Exoskeleton allows paraplegics to walk

“When we started the project, we were a team of gung-ho students who had this cool idea for the lever system. We made some prototypes and were excited about them and brought them abroad and people were like, ‘these are terrible. What were you thinking? You have no frame of reference of what it’s actually like to use a wheelchair everyday,'” he recalls. Over the next few years, he consulted continuously with wheelchair users, and went through several stages of trial and error before landing on the current model.

Winter is currently working with design consultancy firm Continuum on a version of the LFC for the first-world. In all likelihood, it will have more features than the original.

“In the developed world, because there is more disposable income, it’s possible to add additional functionality, things that simply are nice to have but not essential to have,” notes Gianfranco Zaccai, Continuum’s president. The more advanced (and likely more expensive) model, though, “can help support the developing world wheelchair,” he adds.

For Winter, however, the greatest implication of his invention is the platform it has given him to enact even more, farther-reaching change. In a few years, Winter has gone from MIT graduate to assistant professor of mechanical engineering, and director of the University’s Global Engineering and Research (GEAR) Lab, an enterprise that couples engineering and product design to solve real-world problems.

In addition to the LFC, he has delved into how to deliver low-cost prosthetics to poor countries, eco-efficient irrigation systems that enable small-scale farmers to get a higher crop yield and projects related to water purification.

Video: Helping the disabled make music

“I am a total geek,” admits Winter. “I love engineering, I love innovation, and I love being able to work on problems that nobody else has solved before.”

From Stefanie Blendis and Daisy Carrington, CNN