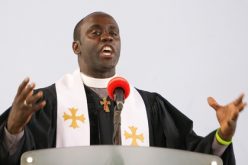

NPR – On a typical Sunday, the pews in Trinity Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C. are almost full. But a few months ago, the large stone church with stained glass windows in northwest Washington, D.C. began looking rather empty. Roughly a quarter of the congregation — 50 people — had stopped showing up.

At first, Rev. John Harmon, the head of the church, wasn’t sure what was going on. Then he started getting phone calls from parishioners. “Some folks called to say, I’m not coming to church because I don’t know who’s traveling [to West Africa],” Harmon says.

The congregation at Trinity is an international crowd. More than 20 countries are represented, including several in West Africa. Reverend Harmon himself was born in Liberia before moving to the U.S. in 1982, when he was 18.

It turns out the fears of congregation members were unfounded — no one from the church was traveling to West Africa during the Ebola outbreak. But some still worried the disease might somehow creep into the church.

At the same time, the church was doing its part to help fight Ebola. Members had raised more than $5,000 and donated medical supplies and protective equipment to West Africa.

But that altruistic spirit didn’t bring the missing congregants back to church. At a service in October, Harmon finally addressed the elephant in the cathedral.

“In the middle of the service, we just had this honest conversation,” Harmon says.

At the time when he would normally deliver a sermon, he instead asked parishioners to voice their concerns. Then several doctors from the congregation talked about Ebola, including how it spreads.

Cora Dixon, a member of Trinity who describes herself as “very concerned about Ebola,” says the doctors were reassuring. “They relaxed our minds,” she says.

Harmon asked anyone traveling abroad to skip church for three weeks — the incubation period of Ebola — even if they weren’t traveling to West Africa. He told everyone it was okay to nod or bow rather than shake hands during the passing of the peace — the part of the service where parishioners greet one another.

Harmon also asked the ushers to put out two big bottles of hand sanitizer. “I use them when I get back to the altar, [as a] visible sign that we are expressing care for each other,” he says.

Since Harmon and other church leaders addressed these concerns, attendance at Trinity has picked back up, almost to pre-Ebola levels. More people are showing up for community service events, too, like a pre-Christmas dinner for homeless people.

Adolphus Ukaegbu, a church usher who is originally from Nigeria, says some members are still avoiding church events because they’re scared of Ebola — including an elderly woman he used to bring to Sunday morning services.

“She told me she was advised not to come to church, because there are so many West Africans in the congregation. And since then, I haven’t seen her,” he says.

But for the most part, things at Trinity are back to normal. And congregants have even started shaking hands and hugging again at the passing of the peace.