Street vendors sell loaves of bread and other wares on a street in Bouake, Ivory Coast, December 2010.

BOUAKE, IVORY COAST — Two years since Ivory Coast’s post-election violence came to an end, rape remains a problem throughout the country. Though such attacks are now occurring outside the context of armed conflict, they show that the security situation for the country’s women remains bleak.

On a recent Saturday morning, Durand Coffi delivered instructions to a moving crew as they cleared furniture out of his ground-floor apartment in Bouake – the second-largest city in Ivory Coast. Though he moved in with his family less than a year ago, earlier this month Coffi decided to leave in search of something more secure.

One night in late April, five armed men broke into the apartment through an unused side door. For the next 90 minutes, they went from room to room threatening the family with pistols while pocketing money and jewelry.

But the worst crimes were committed against two women who live with the family as house help: one was raped by two men in her bed, while the other was raped in the shower where she had been trying to hide.

Coffi didn’t recognize the assailants. He said he was convinced, though, they had been staking out the house for some time before the attack.

“It’s certainly someone who knew me and knew this house. I don’t know them. But they’ve clearly watched me come and go,” he said.

Persistent sexual violence

Sexual violence was a fixture of Ivory Coast’s political crisis, which saw the country divided in half following a coup attempt against then-President Laurent Gbagbo in 2002. Though rebel forces were unable to topple Gbagbo that year, they successfully assumed control over the north of the country, making Bouake their capital.

In a 2007 report, Human Rights Watch documented cases of brutal sexual violence committed by both government and rebel fighters throughout the divided country, including gang rape, sexual slavery and forced incest.

The crisis escalated after Gbagbo refused to accept defeat to current President Alassane Ouattara in the 2010 presidential election – sparking a five-month power struggle that killed thousands. At least 150 rapes also occurred during the conflict, according to Human Rights Watch.

Today Ivory Coast is generally stable, but that doesn’t mean rape has gone away. Rather than occurring in the context of armed conflict, observers say it has instead become a common feature of crimes like armed robbery or is committed as a standalone crime.

As is often the case with rape, comprehensive data is hard to come by. The human rights division of Ivory Coast’s United Nations peacekeeping mission verified and documented 59 cases in the first three months of 2013, but that is believed to be only a fraction of total cases.

Ureported problem

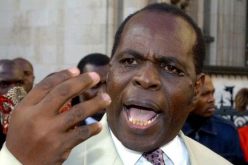

Mohamed Eissa, the chief of the human rights section for the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Bouake, said stigma surrounding sexual violence means rape often goes unreported. His office even has encountered women who, after first reporting their cases to police, have tried to withdraw them as a result of community pressure.

“If you bring the case before the court you will get all kind of difficulty to live in your own community. There is this kind of stigma. You will be isolated. They will give you a very hard time,” said Eissa.

Eissa acknowledged reporting had improved since the end of the post-election conflict, but he said he was convinced there had been an actual recent increase in rape in Bouake – an assertion that was backed up by the local prefect. Eissa said he became convinced of the problem when, after a single night in April, five separate cases were reported in Bouake alone.

He said there were a number of factors that could be fueling an increase, including a growth in population as major institutions in the city, such as the university, resume operations. Another factor is the lack of jobs, leaving young men idle now that the conflict is over.

Social stigma persists

Eissa also said motorcycle taxi drivers have proved to be a particular threat to Bouake’s women in recent months.

“The motorcyclists, they know very well all the small roads and the bush in the city and so on. So when they take a female passenger, if they decide to rape her, they know what to do and where to go,” he said.

That is exactly what happened to Francine, a 26-year-old Bouake resident who was raped in March by a moto-taxi driver.

“I took the moto-taxi, and when we were on our way he proposed a shortcut. And then we arrived at a place where there were no houses. And then I realized he was the only one who knew where we were,” she said.

Like other victims interviewed for this story, Francine said she was eager for police to pursue a case against her unknown assailant.

Local police declined to comment on Bouake’s rape problem for this story, but Eissa said the odds were low that a proper investigation would be conducted.